Copywriters are at their most creative when trying to wriggle out of doing the work at hand. As with the professional salespeople I talked about in my last post, applying a system or methodology to an informal process can help you stay focused. It can also insure that you are not overshooting any decision points in the mind of your reader.

Advertising guidebooks are full of acronymic checklists to verify your copy has a logical flow, such as these three taken from Bob Bly’s excellent The Copywriter’s Handbook:

AIDA = Awareness, Interest, Desire, Action

ACCA = Awareness, Comprehension, Conviction, Action

4 Ps = Picture, Promise, Prove, Push

In each case the process is to make a connection with your audience, then present your selling argument, then go for the sale or other action. If you look at failed advertising, often the problem is that the copywriter got the sequence mixed up—for example, leaping to a sales pitch before you’ve hooked the reader in, or asking for the order before you’ve demonstrated the value of what you have to sell.

My favorite checklist is the one taught by my old client Max Sacks International, and it is something I regularly use in auditing my own work. Since this was developed for use by professional salespeople, I’ll add a translation for copywriters.

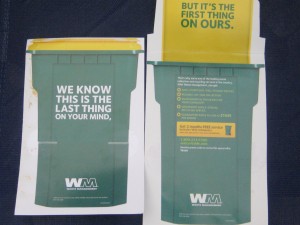

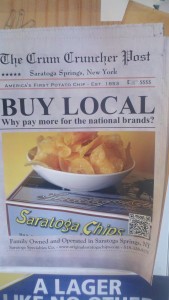

- Approach. How are you going to open the dialog? What will you do to engage your audience?

- Qualification. Make sure the prospect does have buying authority; for copywriters, hopefully the media department has done this job for you.

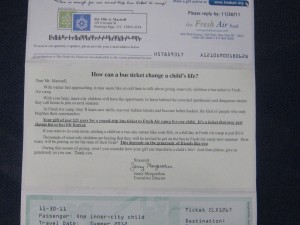

- Agreement on need. Make it clear what you’re talking about, then define a problem to be solved. Easy to do in a face to face environment where you can see a head nod, much harder in the remote medium of copywriting where you have to visualize audience reaction.

- Sell the company. If the prospect doesn’t find the salesperson or the company credible, they aren’t going to buy no matter how appealing the pitch. That’s why you sell the company before presenting your offer. For copywriters this is done with presentation and tone as much as with specific statements.

- Fill the need. Here is the meat of your selling proposition, presented only AFTER every other requirement has been met.

- Act of Commitment. Ask for the order. Tell your reader specifically what you want them to do, and emphasize how easy and risk-free it is to do it.

- Cement the sale. A salesperson will reiterate the commitment that has been made so the new customer does not cancel as soon as they leave the office. A copywriter will do this throughout the message.

Next: why people buy.

Excerpted from my new book, Copywriting that Gets RESULTS! Get your copy here.